Vuelta 2019 Route stage 13: Bilbao - Los Machucos

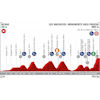

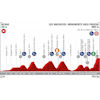

Friday 6 September - At 166.4 kilometres, the 13th stage of La Vuelta is a war of attrition. Following six intermediate climbs the race finishes atop Los Machucos. Or, as the Spaniards prefer to say, 'rampas inhumanas'.

Friday 6 September - At 166.4 kilometres, the 13th stage of La Vuelta is a war of attrition. Following six intermediate climbs the race finishes atop Los Machucos. Or, as the Spaniards prefer to say, 'rampas inhumanas'.

Alto de la Escrita (5.9 kilometres at 4%), Alto de Ubal (7.9 kilometres at 6%), Collado del Asón (13 kilometres at 3.9%), Puerto de Alisas (8.5 kilometres at 6%), Puerto de Fuente las Varas (6,3 kilometres at 4.5%) and Puerto de la Cruz de Usaño (4.2 kilometres at 4.7%). Sounds like a demanding race, right? But that’s basically just the warm up exercise for a brutal finale. The ultimate climb is narrow and painfully steep. Eventual winner Chris Froome found himself on the back foot, while tackling Los Machucos in 2017.

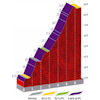

The Spanish are talking about ‘rampas inhumanas’ when referring to the Alto de los Machucos. The Cantabrian mountain is a synonym for torture. The ascent is 6.8 kilometres long and slopes at 9.2%, which is hard enough in itself, but this figure doesn’t tell the story properly. At the bottom of the climb the party begins with a 17.5% ramp before it is followed by a short descent. In the second kilometre the riders stumble upon a 25% gradient, which continues onto a small plateau and yet another crazy ramp (15%). Find a cadence? Forget it! The climb is seesawing between ‘rampas inhumanas’ and 10% descents, although the section between kilometre 3 and 6 is more steady with its average gradient of more than 10%. The climb flattens out near the top, while the ultimate kilometre begins with a drop before a false flat last stretch.

In 2017, Los Machucos was an unprecedented climb in La Vuelta. Attacker Stefan Denifl dragged himself to victory on the narrow track, despite an impressive chase by Alberto Contador. As said, Froome lost time to his opponents – in particular, the blood-smelling Shark of Messina -, but retained the red jersey.

The first three riders on the line gain time bonuses of 10, 6 and 4 seconds, while the intermediate sprint (just before Los Machucos) comes with 3, 2 and 1 seconds.

Another interesting read: results/race report 13th stage 2019 Vuelta a España.

Vuelta a España 2019 stage 13: route, profile, more

Click on the images to zoom

Watch the highlights of recent races here:

Related articles Favourites stage 13: Monster race with brutal finale - Vuelta 2019 The Route - Vuelta 2019 Riders - Vuelta 2019 Withdrawals - Vuelta 2019 Route and stages - Vuelta 2019 Favourites - Vuelta 2019 More articles Summer Olympics 2024 Paris: Route ITT (m/w)

Summer Olympics 2024 Paris: Start list + times ITT – men

Summer Olympics 2024 Paris: Start list + times ITT – women

Summer Olympics 2024 Paris: Route road race – men

Summer Olympics 2024 Paris: Riders road race – men

Summer Olympics 2024 Paris: Route road race – women

Summer Olympics 2024 Paris: Riders road race – women

Clásica de San Sebastián 2024: The Route

Tour de France Femmes 2024: The Route

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 1: Rotterdam - The Hague

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 2: Dordrecht - Rotterdam

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 3: Rotterdam ITT

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 4: Valkenburg - Liège

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 5: Bastogne - Amnéville

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 6: Remiremont - Morteau

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 7: Champagnole - Grand-Bornand

Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route stage 8: Grand-Bornand - Alpe d'Huez

Vuelta 2024: The Route

Vuelta 2024: Riders

Vuelta 2024 Route stage 1: Lisbon - Oeiras

Vuelta 2024 Route stage 2: Cascais - Ourém

Vuelta 2024 Route stage 3: Lousã - Castelo Branco

Vuelta 2024 Route stage 4: Plasencia - Pico Pitolero

Vuelta 2024 Route stage 5: Fuente del Maestre - Seville

Vuelta 2024 Route stage 6: Jerez de la Frontera - Yunquera

Vuelta 2024 Route stage 7: Archidona – Córdoba

Cycling Calendar 2024

Tour de France 2024: Withdrawals

Like our Facebook page and stay on top of all pro-race information!